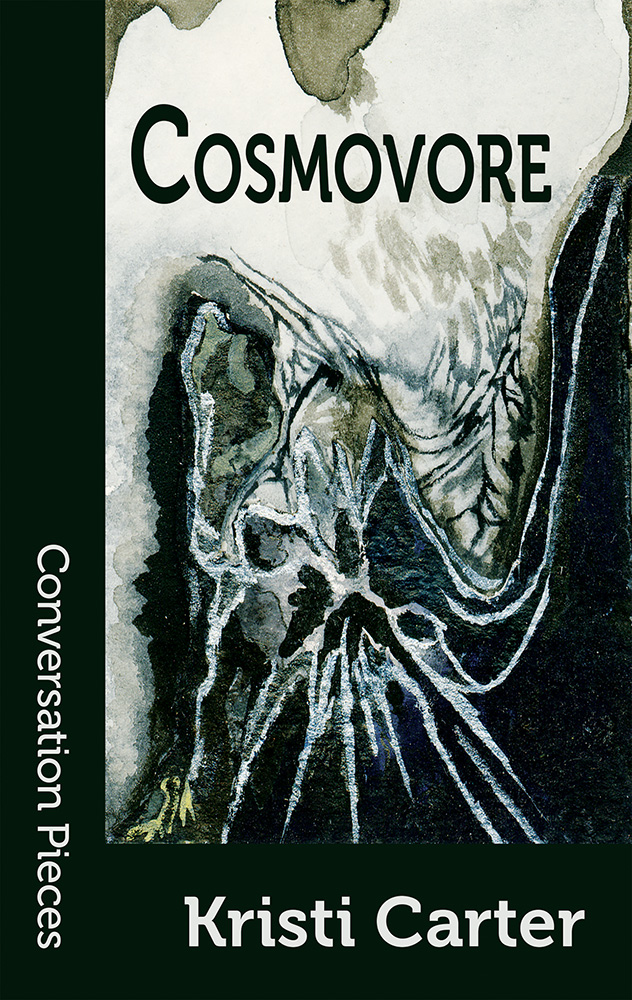

The Q&As with Speculative Poets Series features interviews with writers of science fiction and fantasy poetry about how their work addresses social justice issues. For the first post in the series, I spoke with poet Kristi Carter about her 2017 collection Cosmovore, published by Aqueduct Press.

Kristi Carter is the author of Red and Vast (dancing girl press), Daughter Shaman Sings Blood Anthem (Porkbelly Press) and Cosmovore (Aqueduct Press). Her poems have appeared in publications including So to Speak, poemmemoirstory, CALYX, Hawaii Review, and Nimrod. Her work examines the intersection of gender and intergenerational trauma in 20th Century poetics. She holds a PhD from University of Nebraska Lincoln and an MFA from Oklahoma State University.

Freethinking Ahead: Given that consumption is at the core of the poems in Cosmovore, the book seems to present an argument about the dangers of desire: Cosmovore can have the physical world and incorporate it into herself, but she can’t have her beloved or their child.

What led you to create the character of Cosmovore, her desires, and the ways in which she attempts to satisfy her hunger(s)? And why address those ideas in poems?

Kristi Carter: Thank you so much for starting with this focus on consumption. As someone who has long lived in blue pockets in red states, I’ve seen the way that women are coded as producers, commodities of making more, and the narrative of that repeated as an end goal has reductive implications for women as complex entities. Why is motherhood still an end-goal held above all others in the stories people are fed over and over?

It’s problematic in and of its own to limit women to be the custodians of other people and not have any alternative for their own lives. Considering all that, I think the real match strike for the flame that is Cosmovore was living in Oklahoma when personhood laws for abortions were coming into reality, with little opposition or variety of conversation regarding them. That said, the fatalism I saw in those who disagreed made me turn to poetry as a venue of agency, a kind of activism and alternative to those political choices about what could potentially be my body, in which I had absolutely no say.

Because poetry boils things down to the most essential elements, there is anger, there is hunger for more, and there is an insatiability that seems to reflect how little there is to really pick from.

FTA: One of the aspects of the collection I most appreciate is that it functions on both the literal, speculative level as Cosmovore’s story and on the metaphorical level as an exploration of a woman who loses so much in spite of trying to take as much as she does from the world.

Do you see the subtext of the collection as a critique of what contemporary society deems acceptable (or necessary) for women to want? If so, does that come out of your areas of research?

KC: Oh very much so! Readers who do not question how women are oppressed have seen Cosmovore as a kind of villain or bizarre character. If the conversation is not already happening in the reader’s own life, there is a disengagement from the poems because Cosmovore intensifies questions that are already a burden for most people who want to challenge patriarchal expectations. On the other hand, people who have survived some kind of violence and/or are just fed up with the lack of agency they have respond to those poems on an intuitive level, which is flattering. It’s a divisive collection, just as the issues within are.

In terms of my research, I think it’s no accident to see the reactions of who responds and how. Intersectionality teaches us no one thing about us makes us experience oppression and that our oppressions might parallel those of others and though we cannot always inhabit those differences, and thus empathize, different kinds of marginalization give us different access to those experiences. So for example, I have witnessed more readers who are men of color or LGBTQ men react positively to the text compared to white men. Women react more strongly overall, either in solidarity or in defense of their own attachments to motherhood, or some mixture. When those women are women of color, they react even more strongly. Obviously it depends on the individual, but these trends echo what we have seen in literature and sociology for some time.

FTA: In the poem “Cosmovore Has Night Demons,” Cosmovore contemplates the city around her–and its drive toward consumption through its “open signs […] burned coffee, stale bagels”–as she moves toward thinking about her lost lover and what seems to be their lost pregnancy. She tells him “You never understood anything about survival. About how I could / still be whole / after we lost what I was carrying.” Cosmovore is still a whole woman in spite of her losses.

How do you view this wholeness–if we can see her as whole–in relation to the threads of horror and the fantastic that run through the collection? How did (or didn’t) your idea of Cosmovore change in the course of writing the poems?

KC: The idea of wholeness is really intriguing because it circles back to that idea of goal-fulfillment that influences cultural values, specifically the idea that women have to reproduce to check off some major box validating their existence. When we prod that patriarchal idea with the question of infertility or pregnancy by rape, confusion and aggression seem to arise. Since horror and other modes of surrealism have historically been used to comment on political issues, we witness hyperbolized, condensed narratives about these issues in those traditions.

The sheer power of Cosmovore makes her whole in one sense, but her strength also makes her intimidating. I think it’s a both/and situation that most of us combat in our day-to-day lives where we are told to pick either/or instead. As Cosmovore progressed I saw how again and again deeply engraved that cycle is in the world around us, which is why she is always searching for a kind of release from those confinements.

FTA: Any exciting recent titles (SF poetry or not) that you could recommend to the Freethinking Ahead readership?

KC: A novel I recently read that has been haunting me is Katherena Vermette’s The Break, a recent title which explores issues in the Métis community of Winnipeg, Canada. Vermette is also a poet which comes through in her glimmering prose. For poetry, I recommend Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Heather Derr-Smith’s Thrust, Chloe N. Clark’s The Science of Unvanishing Objects, and anything from the presses that have taken my work. It’s no surprise they make a commitment to the political urgencies of the work they publish as well as the artistic artistry.